|

The

plot of our film today is simple enough:

When three small town California school

teachers drive across the desert to Los Angeles for a baseball

game, along a lonely stretch of road, they come upon a homestead/service-station/salvage yard in the middle of

nowhere; and since their car's engine has developed

a serious hiccup, the driver, Ed

Stiles (Richard

Alden), pulls in to hopefully have

it diagnosed and fixed. No one greets them,

but, it being the weekend

and all, they just assume the station is

closed.

With

nothing else to do while Stiles tinkers

with the fuel-pump on his own, Carl Oliver (Don

Russell) and Doris Page (Helen

Hovey) start exploring the rows of

old derelict cars and empty buildings ... As

they wander about, there are plenty of

foreboding clues that something isn't

quite right -- an empty table with a meal

uneaten, a phone off the hook -- and as

these ominous clues add up, we can't help

but conclude that something sinister is

afoot. Alas, our three heroes are too slow

to put all these effects together before

they're all staring down the barrel of a

.45 automatic...

I

freely admit as a Nebraskan, we as a

state, an entire entity, have an

inferiority complex. We hayseeds and

shit-kickers have a chip on our shoulder

the size of Lake McConaughy (--

buy a map!) and rabidly defend our

place in the union by hoping our lack of

uniqueness somehow makes us unique. What

else do we have to be proud of? Our

biggest claim to fame is having one of the

dullest stretches of any Interstate;

Johnny Carson, Marlon Brando, Henry Fonda,

James

Coburn, and a lot of other famous people

were born here (-- but I point out

they all left); and the

schizophrenic weather, with all four

seasons known to occur within the span of

a few minutes, aren't really

tourist attractions, either.

And

then there's that whole Charlie

Starkweather thing. E'yup, we had the

nations first fugitive spree killer. Yay

us. For those few who are unfamiliar

with this yahoo, back in 1958, nineteen

year-old Starkweather and Caril Fugate,

his fourteen year-old girlfriend,

terrorized the nation's heartland as they

blazed a trail through five states,

leaving another trail of dead bodies

behind them -- eleven people all together,

including

Fugate's parents and baby sister, whom

Chuckles beat to death -- before

finally being caught. My mother, who was

twelve years old when these two were

running amok, honestly doesn't like

talking about it all that much; it scared

her pretty good. What little she

recollected was that the deadly couple were

[allegedly] spotted in the nearby town of

Hastings at one point -- as I'm sure they

were [allegedly spotted] in

every town at the time, and how her folks

kept both doors locked and a shotgun, also

locked and loaded, stationed by each.

Everyone was scared, for this was a whole

different kind of gun nut than, say,

outlaw bandits like Bonnie and Clyde, or

John Dillinger, who came before them.

After they were finally caught, Fugate

turned against her boyfriend, claiming to

be a hostage the whole time, but nobody

bought her story. For their crimes,

Starkweather got the electric chair, Fugate got a life sentence, and teenage

delinquency had taken a new, and

dangerously lethal turn. And advocates against

things like rock and roll music, violence

in the media, and the decline of moral

values had a new poster couple to vilify

as a new phrase entered our pop-culture

lexicon: the thrill-killer.

Over

the subsequent years, Starkweather and

Fugate's homicidal relationship served as

the basis for several films, most notably

Terrence Mallick's Badlands,

and its influence spawned a whole genre in

the 1990's about trailer-trash with guns

with films like Kalifornia

and Oliver Stone's Natural

Born Crackers

-- erk, I mean, Natural

Born Killers.

Still, Badlands

debuted almost fifteen years after

Charlie got the chair. Seems mainstream

Hollywood was reluctant to tackle the sore

subject of this new breed of mass

murderer; and while they wouldn't touch

the likes of Starkweather, Richard Speck

or Charles Whitman with a ten-foot pole,

many a smaller, independent production

companies were, forgive me, quicker on the

trigger. And one

of the first fledgling adaptations came

out in 1963 by the anti-dynamic duo of

Arch Hall2 -- a/k/a Arch

Hall Sr. and Arch Hall Jr. And judging by

what they'd done before, cinematically

speaking, you never would have guessed

they'd have this good a movie in them.

Coming on the heels of EEGAH!,

their

giant caveman on the loose epic,

came this criminally underrated gem of a

film: an honest study in unbridled

brutality and mounting terror called The

Sadist.

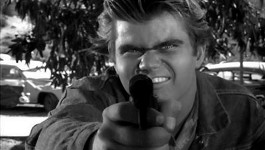

Now,

the

finger on the trigger of that .45

automatic I described earlier belongs to

Charlie Tibbs (Arch

Hall Jr.), a thug of the highest

caliber. With his jailbait girlfriend,

Judy Bradshaw (Marilyn Manning)

on his arm, Tibbs starts to torment this

hapless trio of travelers. Doing her best

to encourage him, Judy constantly whispers

into his ear, egging him on, and giving

him ideas that are the equivalent of

somebody pulling the wings off of a fly

before squashing it. Quite obviously,

Charlie relishes his position of power,

especially when he finds out his latest

batch of victims are all

teachers -- and is amped up even more by

the cowed reaction of his captive

audience.

Stiles

realizes first that these two are the

spree-killers that have been making

headlines lately, blazing a trail of

robbery and murder through three states.

Tibbs doesn't deny it and gladly gives a

play by play on how they wound up here, in

the middle of nowhere, stranded with a

broken down car (--

that was stolen after they killed the

owner); and they had just killed

the gas station owner and his family when

they heard the teachers pulling in.

Itching to move on, Tibbs already has his

beady little inbred eyes on their car until Stiles warns

the fuel pump is shot. Knowing

they're all on borrowed time, he offers to

fix it -- with a hope to stall things

along until they can engineer an escape. Tibbs

agrees, but makes no secret of his

intentions to kill them all as soon as the

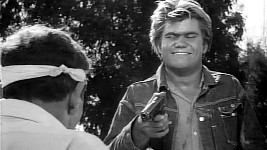

car's fixed. When Oliver, the eldest of

them, tries to reason with their captor, he only

gets pistol-whipped for it. Then, turning

a lecherous eye toward Doris, Tibbs

playfully uses her and Oliver for a little

target practice until Stiles refuses to do

any more work unless he leaves them alone.

But Judy has a better idea, anyway, and whispers

it into Charlie's ear. Liking the idea, he

makes Oliver get on his knees and beg for

his life; and he only has a narrow

window to make his case -- he has however

long it takes Tibbs to finish a bottle of

soda-pop before his life will end! And as

he knocks the bottle back, again and again,

Oliver's pleas for help from his friends

and mercy from the hoodlum prove

fruitless. The bottle soon empty, Tibbs

cocks the trigger and thrusts the gun

right into his victim's face!

This

is the critical point in The

Sadist,

and it's a pivotal moment for the

audience, too. Things begin creepily

enough: there are plenty of ominous clues

that we're made aware of, as an audience,

but not our protagonists that something is

wrong --

the cut phone lines, signs of a

struggle, and just an overwhelming sense

that they're being watched by something.

Things quickly turn sinister, confirming

our suspicions, when a .45 is thrust on

screen, taking up the whole frame; then

the camera whirls around and we're

suddenly face to face with our

"sadist" -- whom we B-Movie

zealots quickly recognize as the

unmistakable mug of Arch Hall Jr. ... Arch's

performance as Charlie Tibbs is anything

but restrained, and over the top doesn't

even begin to do it justice. He strikes

odd poses with the gun, and his voice and

inflection come off as slightly retarded

as he starts to put our heroes through the

wringer, physically and emotionally. And

you get the first uneasy inkling that this

film is a different breed of J.D. thriller

when Tibbs goes through the groveling

Oliver's wallet, first tearing up his

baseball tickets, and then pictures of his

family. This sense of uneasiness is

reinforced when he accosts Doris and

actually sticks his hand up her shirt and roughly

cups a feel.

Whoa

-- What the hell? Can this truly be

happening? Is

Arch Hall Jr. actually being menacing? Well ...

Arch's ham-fisted delivery still has us

harkening back to his other juvenile

delinquent pictures, like The

Choppers,

and other authoritarian, albeit hilarious,

entries in this particular genre. I'll

admit, up to this critical point, I was

laughing at old Arch, too. With

that high-pitched voice and perpetual

squint, all topped off with that concrete

pompadour,

his performance, for some reason, was

reminding me of a young and pudgy Wayne

Newton (--

back when he was doing guest spots on Bonanza).

But

then we reach that pivotal moment when

Oliver's time runs out:

Ignoring the pleas

for mercy...

Tibbs, with the .45

in hand...

Sticks

it point plank in Oliver's face...

And

pulls the trigger.

*Bang*

Holy

crap! What the hell just happened?

Like

Tibbs, the camera doesn't flinch. We see

the whole thing. Here, I'll

pause to remind everyone that this is

1963 we're talking about; and I'm

curious if this is the first time we

actually see someone get shot in the

head without the aid of a jump-cut.

And

after that extremely shocking moment,

everything afterwards, even though Arch's

character is doing the exact same things, and he's acting the exact same way,

everything that seemed silly and insipid

before honestly becomes chilling, and, in

some cases, downright terrifying!

In

an Arch Hall Jr. flick?! Are you kidding

me?!

No.

I'm not. And

I'll even take it one step further and say this

whole movie is pretty damned good, even though

it's become cliché, retroactively;

spoiled by a lot of

psycho-degenerate/white-trash serial

killer films that followed. Is that fair?

I don't think so. Some people are just

narrow-minded these days. And yeah, it is

hard to believe when you look at the

Arches' oeuvre as a whole ... See, Arch

Hall Jr. was the protégé of his father,

Arch Hall Sr. After getting out of the

military (--

and his time in the service as a test

pilot was actually made into a film by

Jack Webb, of all people, in The

Last Time I Saw Archie),

Senior became an independent movie

producer, mostly second-tier westerns. He

also served as writer and director on a

lot of his projects and eventually founded

his own company: Fairway International

Pictures. And in that capacity, he was

also responsible for giving Ray Dennis

Steckler his first directing gig (--

and god bless 'em for that! Arch Sr. also

produced Steckler's similar, but not quite

as effective, The

Thrill Killers.)

When

westerns began to fade at the box-office,

Senior switched his production-eye toward

the exploitation market and backed a

nudie-cutie written by Junior called The

Magic Spectacles.

Senior also saw the success that American

International Pictures was having with

their swinging beach party movies and hit

upon an idea...

All

Arch Hall Jr. ever really wanted to be was

a pilot, like his dad, but Senior got it

into his head that he could turn his son

into a crooning teen heartthrob -- a

cash-cow, and over the span of three short

years assaulted the drive-in circuit with

the critically low-budget

"classics" The

Choppers,

Wild

Guitar

and EEGAH!.

Each

movie proved successful enough to form the

budget for the next one. They're

all pretty terrible -- but a demented good

time, which probably explains why Arch

Hall Jr. never really took off.

With

all the perceived acting talent of an avocado,

coupled with musical talents that could

barely muster songs like "Kongo

Joe" and "Monkey in My

Hatband", Junior's career quickly

petered out with The

Nasty Rabbit

and Deadwood

'76.

He then gave up acting altogether, went

on to get his pilot's license, and became a

successful commercial aviator. Senior, who

had been a modestly successful independent

film producer, was crushed by this

development, and, according to Steckler in

the book

Research

10: Incredibly Strange Films,

was never the same. When Junior walked

away from the movie business, Senior

stopped producing, too, and the world of

B-movies is lesser for it. (Arch

Hall Sr. died in '76.)

At last report, Junior is still flying, is

a grandfather, and living in Florida but

declines most offers to discuss his film

career. I also understand that he's just

published a novel under one of his

father's many pseudonyms.

Right

in the middle of all that cinematic cheese

came The

Sadist,

but it was two other men, I believe, who should be

properly credited for elevating this movie above

the rest of the dreck: James Landis and

Vilmos Zsigmond. Arch Sr.

served only as the producer (--

and as the uncredited narrator, Nicholas

Merewether) on this flick, while

the writing and directing chores fell to

Landis. A veteran writer for the TV show Combat!,

Landis took the no-nonsense, documentary

approach of that show and applied it to The

Sadist.

As the first serious attempt to adapt the

Starkweather and Fugate murder spree on

film, Landis proved up to the task, and

his simple, matter-of-fact style resulted

in pretty taut thriller that will knock

you right on your ass because this is the

last thing you're expecting when you see

who's on the marquee. Zsigmond, here

billed as William Zsigmond, served as the

film's cinematographer, and his set-ups

and creative framing give The

Sadist

a certain frenetic look -- a razor-blade

starkness, and a down and dirty grittiness

that gives the film most of its cinematic

punch. He keeps switching perspectives:

one minute we are on one side of the gun

looking down the sight, the next we're

staring right down the barrel; it's simple

but effective in keeping us off balance.

There's a lot of effective handheld camera

work, too, getting us down in the dirt and

the middle of the action -- I swear the

camera barely gets over three-feet off the

ground for the majority of the picture,

and the frame never really does stand

still once the ball gets rolling, giving

this film a frenzied sense of momentum that

keeps things barreling toward the climax.

Zsigmond

is another one of those gifted craftsmen who

worked their way up the film food chain.

Breaking in with the Arches, he moved on

to work with Steckler for several

pictures, including The

Incredibly Strange Creatures who Stopped

Living and Became Mixed Up Zombies,

where he worked with two other famous

contemporaries, Lazlo Kovacs and Joseph

V. Mascelli; then Al Adamson's Satan's

Sadists, before graduating to

more mainstream work for the likes of Robert

Altman, John Boorman and Steven

Spielberg, and eventually, an Academy

Award for his craft with Close

Encounters.

He ran into a streak of bad luck after

that, though, with the critical and

box-office disaster Heaven's

Gate

and several Brian de Palma duds,

including Bonfire

of the Vanities. Now

back to the review!

When

combining their efforts, here, these two

concoct a film that is relentless, brutal

and very downbeat that definitely deserves

more notoriety. So why don't more people

know about it? And why isn't it considered

a cult movie classic? Well,

with all respect to Arch and his gonzoid

performance, it is the cast that

ultimately sinks the film. Mention of a

positive nature should be made for Marilyn

Manning's equally understated

performance as Judy -- and it's hard to

believe that these two played the two

brain-dead teenagers in EEGAH!

just the year before. As Tibbs's deadly

muse, she seems to be the true trigger for

his homicidal outbursts. To her it's just

a game, and her sinister suggestions and

the scenes of her rifling the dead for

souvenirs is truly disturbing. So

that means the biggest problem lies with

our three protagonists. These characters

are paper thin to begin with and the

actors don't really add anything to them.

Russell fails as the voice of reason and

both he and Alden appear to have gone to

the William Shatner school of acting.

You'll occasionally catch a hint of an

accent from Hovey, a cousin of the film's

star. She's a gamer, but never acts like

she's in any real danger, like she hasn't

quite got the difference between acting

and pretending down yet, so some of the

menace is lost. And as the film plays out,

dare

I say Alden makes a better "final

girl" than she does? And to

be honest, there are no likeable

characters here. Well, Carl Oliver, maybe,

but he's already dead. I mean, Tibbs and

Judy, our thrill-killers, are sociopathic

vermin, and Stiles comes off as a

sniveling coward, while Doris is, well, as

I hinted before, Doris is kind of a

helpless cipher who you'll be yelling

"Run, ya idiot!" at. A lot.

And

there are several chances to escape, or

take Tibbs on, but Stiles keeps wimping

out -- but it is a believable kind of

wimping out, so we can empathize with him

a little. The biggest chance to escape

comes when two passing motorcycle

patrolmen stop for some refreshments.

Alas, the protagonists wait too long to

warn them, letting Tibbs get the drop on

the cops, and he shoots them both dead. And

with each dashed hope and every missed

opportunity continuing to stack the deck

against our survivors' life-expectancy,

you're still conditioned to expect a happy

resolution -- but it never comes. Evil

isn't punished in the film. Evil only kind

of devours itself; a hollow victory for

the good guys. It

starts with a deft move by Stiles, who

finally summons the courage to act,

and then Tibbs, his face full of gasoline,

accidentally shoots and kills his partner

in crime. Up to this point, as I said

before, Stiles had

kinda been a cowardly weasel, but you

figure now that he's finally grown a pair,

he'll come through and save the day, thus

redeeming himself. And, like Stiles, I was

counting the number of shots while Tibbs

was chasing him. So after their harrowing

game of cat and mouse, when the gun clicks

empty and Stiles goes on the attack -- and

we as an audience look forward to seeing

Tibbs finally getting his head kicked in

-- we, like Stiles, forgot about the

stolen police revolver, and then sit in

stunned silence when Tibbs pulls the

second gun and drops his latest victim before he can

even get close. And there will be no

last-second heroics by a wounded Stiles,

either, as Tibbs empties the revolver into

him, punctuating that point with a

gruesome finality.

Then, after another prolonged

stalk and chase scene (-- that

we'll be seeing again twenty years later

in Texas, if you know what I mean),

Doris is saved by dumb luck and dumb luck

only when Tibbs falls into an abandoned

well, a den for several rattlesnakes,

which robs of us of any kind of emotional

payoff. And we end with Tibbs's death

screams (-- that purposefully sound

like a dying animal --) as Doris, in a

state of shock, slowly wanders back toward

the junkyard as those resonating, primal

shrieks fade to be replaced by the radio

call of the baseball game.

And

that is why you'll have a hard time

shaking The

Sadist

once you've seen it, because you're angry

at it -- and in hindsight, respecting the

hell out of it -- for cheating us out of

any kind of vindicated resolution. Just

one of the many reasons why The

Sadist

truly is a remarkable and groundbreaking

piece. And its influence can be seen in

the relentless, cynical and brutal horror

films of Craven, Hooper and many others in

the 1970's and should be championed for

this and not lampooned because if its

leading man. Facts is facts: The

Sadist

was the first of it's kind, and definitely

deserves to be better known than it is.

|