|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1973) Director: Oscar Williams

For years, blacks kept getting the short end of the stick in Hollywood, both in front of and behind the camera. Then in 1971, Shaft hit theaters and became a huge hit, earning enough to be the twelfth-highest grossing movie of that year. Naturally, since Hollywood loves to go where the money is, executives from various studios took notice and soon were churning out their own black-themed movies. Some have said that it was thanks to these "blaxploitation" movies that today's black actors and directors have the power they do in Hollywood... though some have claimed otherwise, pointing out to the state of black-themed moviemaking for years after the blaxploitation genre died off in the mid '70s. But backtracking several years before that happened, black audiences were finally being given black-themed movies on a regular basis. No doubt you have heard of a lot of these movies - Foxy Brown, Superfly, The Mack, Cleopatra Jones, and Black Caesar are just five examples of the blaxploitation genre that were not only big hits in their days, but are still popular with fans today. Though looking at those five movies as well as other efforts put out in that era, you start to sense a pattern, and its one that upset many black leaders. Although these leaders were certainly thrilled that blacks were finally being given work in front of and behind the camera, they were upset that these movies were almost entirely exploitive in nature, involving violent action as well as other adult-themed elements such as nudity and sex. American-International Pictures made a number of these

blaxploitation movies, many of which are among the best-known. Film

head Samuel Z. Arkoff wrote years later in his autobiography about an

incident when the leader of one black organization complained that

these black-themed movies focused on "cops and criminals" instead of

black families. Arkoff was not without sympathy towards the struggles

of blacks in Hollywood - in fact, A.I.P. was actively involved in

getting blacks accepted into various Hollywood unions - but Arkoff laid

the facts straight to the The recent release Barbershop was indeed a more realistic look at a section of black American society, but the reason why it was a hit was because it had plenty of comedy added to its story, with situations and characters that were believable yet spun around to be amusing in many different ways. But you don't have to look at the present day for more realistic looks at black society. In fact, the blaxploitation era did manage to put out a few of its own, among them Sounder, Cooley High, and A Hero Ain't Nothing But A Sandwich. One of the other more serious looks at American black society during this era was Five On The Black Hand Side, based on a stage play by Charlie L. Russell (who also wrote the screenplay.) It was different from other black-themed movies of the era not just because it was a more believable depiction, it was extremely proud of the fact and not afraid to show it. The movie loudly proclaimed to audiences, "You've been Coffy-tized, Blacula-rized and Superfly-ed - but now you're gonna be glorified, unified and filled-with-pride... when you see Five On The Black Hand Side!" in its trailer and on the movie poster. (Whether this lead to box office success or not is something I have been unable to find out.) The movie takes place in Los Angeles, centering around the Brooks family. It's a particularly chaotic time in the household when we first meet them - daughter Gail (Bonnie Banfield) is going to be married in two days. Eldest son Booker T. (D'Urville Martin, Dolemite) is in the middle of a rebellion against the system, changing his "slave name" to Sharrief and preaching both Mao and revolution. Younger son Gideon (Glynn Turman, A Different World) also is against the white power structure, but his rebellious behavior is more personal - he is refusing the demands his father has made, and is currently living on the roof of the apartment building as part of his protest. John Henry (Jackson, Shining Time Station) is the patriarch of the family, a stern and stubborn man not far removed from George Jefferson. Having grown up in the Depression and struggled in the traditional way for years to end up relatively successful as a barber with his own shop, he can't understand why his children want to do things different than him. "Why must you have an African wedding?" he grunts to Gail, saying that he doesn't understand these new-fangled "foreign ways". Not only that, instead of discussing with Gideon his decision to not follow his father's expectations to get a business major (instead turning his studies towards getting a degree in anthropology), he instead writes a big-worded and formal-sounding letter of ultimatum, listing his repeated demands. To top it off, he doesn't even give that letter directly

to Gideon or even leave it in a There's more than that that is happening at that time, and more that happens later on, so you certainly can't say Five On The Black Hand Side is boring - far from it, as a matter of fact. I certainly felt I got my money's worth with this movie even before the end credits came up. But although all of this "stuff" certainly adds to the amount of entertainment to be found and enjoyed in the movie, at the same time it seems to be one of the primary causes of one of the movie's problems. With so much happening in this movie, there doesn't seem to have been enough time to properly resolve things. I'm not just talking about one or two subplots - it seems that every subplot feels unresolved to one degree or another. For example, there is a serious sequence in the middle of the movie involving Gideon confronting Booker T. about his secret white girlfriend. The argument gets quite heated, almost getting to the point of true violence, and though both brothers are simmering down when the confrontation ends, you can still tell the issue is not resolved with both of them. You get the feeling this issue will be resolved later, but not only does that not happen, the issue isn't even really brought up again. Some other issues do get to a proper resolution, but

along the route from the time the issue is first brought up to its

resolution, important transition points get bypassed. Given this movie

has a generally light-hearted viewpoint, I don't think it comes as a

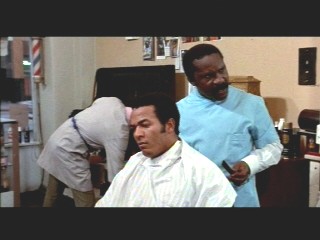

surprise whether Gladys proves victorious or not. Though the screenplay definitely could have used an extra rewrite or two, the various holes scattered throughout at least don't diminish the fact that there is still plenty to enjoy in the movie. Though the journeys of the various plots may not reach their seemingly intended destinations, at least each interrupted journey manages to keep your interest while it lasts. One substantial part of the movie doesn't even seem to have any real purpose, yet it happens to be one of the best parts of the movie. That part concerns the going-ons at John Henry's barber shop, with John Henry and his barber employees interacting with the various customers. It's completely plotless, yet their constant ribbing and joking around is very funny. (In fact, I am confident that the makers of Barbershop were inspired by this segment of the movie.) Their various personalities and backgrounds - the conservative John Henry, a couple of senior citizens, the college-educated Preston (Dick Williams, Hot Boyz), the numbers runner "Rolls-Royce", and the happy-go-lucky "Fun Loving" all interacting together in the same small room provide some great laughs, but also more. The verbal banter reveals that they all have different opinions and philosophies, yet they get along all the same. In fact, the idea of finding common ground is a repeated

message throughout Five On The Black Hand Side. While

the primary goal of the movie does seem to entertain, it also finds the

time to bring up some serious subjects, presenting Not all the serious moments in the movie contain a "message" or something to think and ponder about. There is also some simple human drama, the best being the closing wedding sequence. Though the wedding has a definite African flavor to it, with the couple and most of the guests dressed in traditional clothing, there is at the same time a beautiful simplicity to it - many weddings forget the ceremony is about two people getting married, and not about the fancy dressing attached to it. It's performed in a small community hall, with only folding chairs and a couple of tables with cake and punch brought in, but it doesn't seem cheap or tacky. With nothing distracting up, our eyes stay on the happy couple. At the same time, our ears are fixed on the beautiful words the minister utters, telling both the bride and the groom what responsibilities each of them must agree to if they not only want to be married, but to stay married in a strong and fruitful marriage. Love, yes, but be responsible and supporting despite any differences. That's a message you hear time and again in this movie, but this isn't a "message movie" in the normal sense. Obviously writer Russell knew that being that way would not only make his story contrived, audiences, wanting to be entertained, would be turned off instead. His ear for dialogue, both comic and serious-but-interesting, more than makes up for the plot holes as well as for some production flaws coming from the (obvious) low-budget, and makes for a movie that viewers of any race can appreciate.

Check for availability on Amazon (VHS) See also: The House On Skull Mountain, Kenny & Company, That's Black Entertainment |

protester.

"Audiences just don't go to see pictures about families, whether the

families are black or white. Unfortunately, moviegoers aren't drawn to

films that show normal family life, unless they are romantic or comedic

in nature." Arkoff was pretty dead-on with that statement, in my

opinion. A moviegoer who is going to shell out several bucks not only

wants to see enough "stuff" of some kind in order to get his money's

worth, he also wants to escape from reality for 90 minutes or so.

protester.

"Audiences just don't go to see pictures about families, whether the

families are black or white. Unfortunately, moviegoers aren't drawn to

films that show normal family life, unless they are romantic or comedic

in nature." Arkoff was pretty dead-on with that statement, in my

opinion. A moviegoer who is going to shell out several bucks not only

wants to see enough "stuff" of some kind in order to get his money's

worth, he also wants to escape from reality for 90 minutes or so.  place where Gideon

will see it - instead, he hands the envelope to his wife Gladys Ann

(Taylor, The Cosby Show) with the order to give it to Gideon.

We soon this is just one of the many burdens John Henry has put on his

wife. Always calling Gladys "Mrs. Brooks" instead of her first name,

John Henry is a true male chauvinist. Not only does he tell poor Gladys

what she can or cannot do and leaves all the responsibilities of the

household onto her, he even writes in her appointment book what

recreational activities she should do during one of her rare chances at

free time. This has been going on for years, and Gladys has reached the

breaking point. She confides to her neighbor and friend Ruby (Capers)

she long ago made a vow that once all her children were grown up and

able to take care of themselves, she would "leave Mr. Brooks." Another

friend of Ruby, the sassy "Stormy Monday" (Ja'net DuBois, Good Times)

happens to be around that particular day, and she shoots down Gladys'

plans, pointing out the obvious problems that would come up from

leaving. But seeing how unhappy and cowed Gladys is, she then proposes

an interesting idea: If Gladys can't change John Henry, why doesn't

Gladys try changing herself? So while John Henry works and laughs it up

with his employees at his barber shop, Stormy Monday and Ruby being

work on Gladys, starting with a new hair style, but soon doing a lot

more to give her some much-needed backbone.

place where Gideon

will see it - instead, he hands the envelope to his wife Gladys Ann

(Taylor, The Cosby Show) with the order to give it to Gideon.

We soon this is just one of the many burdens John Henry has put on his

wife. Always calling Gladys "Mrs. Brooks" instead of her first name,

John Henry is a true male chauvinist. Not only does he tell poor Gladys

what she can or cannot do and leaves all the responsibilities of the

household onto her, he even writes in her appointment book what

recreational activities she should do during one of her rare chances at

free time. This has been going on for years, and Gladys has reached the

breaking point. She confides to her neighbor and friend Ruby (Capers)

she long ago made a vow that once all her children were grown up and

able to take care of themselves, she would "leave Mr. Brooks." Another

friend of Ruby, the sassy "Stormy Monday" (Ja'net DuBois, Good Times)

happens to be around that particular day, and she shoots down Gladys'

plans, pointing out the obvious problems that would come up from

leaving. But seeing how unhappy and cowed Gladys is, she then proposes

an interesting idea: If Gladys can't change John Henry, why doesn't

Gladys try changing herself? So while John Henry works and laughs it up

with his employees at his barber shop, Stormy Monday and Ruby being

work on Gladys, starting with a new hair style, but soon doing a lot

more to give her some much-needed backbone. However, we can't

enjoy Gladys' triumph as she does, because we never see the

triumph. In one scene, John Henry is his typical sexist and ornery

self, then in the next scene we learn that he gave into Gladys'

demands. What caused him to finally crack? Did he really have a change

of heart towards Gladys after she stood up to him, or is he really the

same stubborn man but is just restraining his real feelings? It's

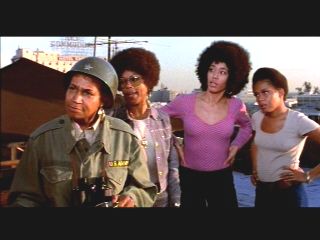

difficult to tell. For that matter, Gladys' transformation from a woman

easily moved to tears to a woman who struts around confidently in a

military uniform while dictating orders in a walkie-talkie to her

sisters-in-arms is also equally sudden and unexplained. I have no idea

if this unfinished feeling was in the original stage play or not.

Possibly a lot had to be taken out so that the movie wouldn't be too

long, but there are also a lot of moments that were obviously never in

the original stage play, such as the fender-bender sequence that seems

to have no purpose except to contain a gratuitous cameo by Godfrey

Cambridge (The Watermelon Man), who actually plays

himself in this sequence.

However, we can't

enjoy Gladys' triumph as she does, because we never see the

triumph. In one scene, John Henry is his typical sexist and ornery

self, then in the next scene we learn that he gave into Gladys'

demands. What caused him to finally crack? Did he really have a change

of heart towards Gladys after she stood up to him, or is he really the

same stubborn man but is just restraining his real feelings? It's

difficult to tell. For that matter, Gladys' transformation from a woman

easily moved to tears to a woman who struts around confidently in a

military uniform while dictating orders in a walkie-talkie to her

sisters-in-arms is also equally sudden and unexplained. I have no idea

if this unfinished feeling was in the original stage play or not.

Possibly a lot had to be taken out so that the movie wouldn't be too

long, but there are also a lot of moments that were obviously never in

the original stage play, such as the fender-bender sequence that seems

to have no purpose except to contain a gratuitous cameo by Godfrey

Cambridge (The Watermelon Man), who actually plays

himself in this sequence. them and discussing

them in an equally serious manner. Take that previously mentioned scene

when Gideon confronts Booker T. about his secret white girlfriend.

Gideon, recalling he's never seen Booker T. with a black woman, accuses

his activist brother of being a hypocrite, stating "How can we build a

nation of strong families without [black women]?" Booker T. counters

this by claming that up to this point he simply hasn't met an available

black woman having the specific qualities that he finds appealing.

Besides, he feels something personal like who someone dates is just

their business only, period. Clearly, both men have valid points.

Nobody is perfect in the Brooks family, just like real life. Though

Gladys has reason to stand up and fight back, some of her later

tactics, like publicly humiliating her husband, seem excessive. But

nobody is a complete ogre as well. Though John Henry initially comes

across as cold-hearted and stubborn, we find he has some good in him.

We eventually find out John Henry wants Gideon to go in business

because he feels it would give Gideon the best chance for success, not

because it had been John Henry's dream when he was young. John Henry

may sneer at the idea of black unification, but we learn that he

achieved success (like a barber shop fully paid for) all by himself -

all done before blacks had all the rights they have now.

them and discussing

them in an equally serious manner. Take that previously mentioned scene

when Gideon confronts Booker T. about his secret white girlfriend.

Gideon, recalling he's never seen Booker T. with a black woman, accuses

his activist brother of being a hypocrite, stating "How can we build a

nation of strong families without [black women]?" Booker T. counters

this by claming that up to this point he simply hasn't met an available

black woman having the specific qualities that he finds appealing.

Besides, he feels something personal like who someone dates is just

their business only, period. Clearly, both men have valid points.

Nobody is perfect in the Brooks family, just like real life. Though

Gladys has reason to stand up and fight back, some of her later

tactics, like publicly humiliating her husband, seem excessive. But

nobody is a complete ogre as well. Though John Henry initially comes

across as cold-hearted and stubborn, we find he has some good in him.

We eventually find out John Henry wants Gideon to go in business

because he feels it would give Gideon the best chance for success, not

because it had been John Henry's dream when he was young. John Henry

may sneer at the idea of black unification, but we learn that he

achieved success (like a barber shop fully paid for) all by himself -

all done before blacks had all the rights they have now.